The Pipeline Problem: How Talent Selection Becomes a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

Part 3 of a series of articles on developing players by Rein van Eijk, head coach of the Belgian national women's team

A follow-up to “More Than Talent” and “The Ones We Leave Behind”

In earlier pieces, I wrote about the players who fall through the cracks — not because they lacked the will, but because the system closed the door too early. And I explored how culture can either help talent grow or quietly squeeze it out. This time, I want to go deeper into that system itself. Into the hidden logic behind early selection. Into the way we build our teams, structure our pathways, and unknowingly create a pipeline problem — one that often turns our predictions into self-fulfilling prophecies.

The Selection Illusion

Research has shown that early selection can significantly influence developmental trajectories, often not because of inherent talent, but because of the opportunities that follow initial selection (Vaeyens et al., 2009). This is particularly problematic in sports where physical maturation varies widely during adolescence. There’s a quiet logic in youth sport that most coaches never question.

Group the best players together. Give them the best coaching. Let them train at a higher level. Their development will skyrocket — and the team gets better faster. Win-win.

But grouping the best players means something else, too: it means pulling out those deemed less good at that moment in time. It means removing them from the environment that accelerates development — and in doing so, it narrows the pipeline. Not because we’re bad people. Because the system is built that way.

And it’s not wrong. That logic holds, at least in part.

But here’s the deeper problem: if we want to give players a real shot at making it to the next level, we can’t afford to pull them out too early. The longer we keep players in the group, the more chance we give them to grow. And yet, the moment we separate them, we dramatically reduce their odds of catching up — not because they lack talent, but because they no longer get the same environment to develop in.

The Compounding Effect of Environment

The principle of the 'Matthew Effect' — where the rich get richer — also applies to talent development (Merton, 1968). Players in top environments benefit from better coaching, facilities, and peer interactions, which compounds their development advantage. The environment does the work. And we pretend it’s the player.

In every group, performance is shaped by intensity, feedback, peer influence, and motivation. A player who trains with sharper peers every day improves more quickly — not just technically, but cognitively, socially, emotionally. The bar is higher. The mirror is clearer.

Meanwhile, the player left out of the top group? They work just as hard. Maybe harder. But the learning curve is flatter. Less challenge. Less exposure. Less feedback. Over time, the gap grows. And we point to that gap and say, “See? That’s why they didn’t make it.”

But the truth is, they might have never really been given a fair chance to make it back.

That’s something I’ve wrestled with personally — and professionally. In Berlin, we really built a program from the ground up. And now, with the Red Panthers in Belgium, I feel I’ve stepped into another one — a system built deliberately, not just a team formed around available talent. I’ve seen what thoughtful structure can do. And I’ve also seen what happens when good intentions still lead to early exclusion.

A System Built to Widen the Gap

Just last week, a coach asked for my thoughts about how to bridge the gap between a first and second team. The conversation turned, as it often does, to training schedules: second-team players joining only one or two first-team sessions a week, to preserve their presence in the second team. It sounded like a compromise. A practical one.

But here’s what I’ve noticed over the years: the more we justify these compromises, the less sense they start to make to me. Not just ethically — but logically.

In most clubs, academies, or player pathways, first teams typically get more training sessions, better resources, and age-specific coaching. Second teams still train — often at the same time. But if a second-team player wants to join a first-team session, they usually have to skip their own. or, worst case, those sessions overlap, and the player from the second team therefore cannot join the first team's practice, the path to the top narrows even more — because the opportunity to be exposed to a higher development environment is taken away before it even begins.

Add to that the classic arguments: “They’re not ready for this level,” or “They’ll bring the group down.” Sometimes even, “The others don’t like training with them.” We create false narratives — using peer opinions to justify excluding players who are simply still developing.

Growth for Some, Not All

Back when I was coaching the regional selection team for South Netherlands Boys U14, I remember attending a lecture in the mid-2000s by Marc Lammers. He spoke passionately about how to bring more talent through from the Brabant region — a message that stuck with me as we were re-building our talent centre in the south of the Netherlands. His message was clear: if you want better players, have them play more — with and against the best. Because sharpness breeds sharpness. It stuck with me.

But here’s the catch: that logic only holds if we’re willing to give the so-called “lesser” players a chance to be in that environment too. Otherwise, we’re just reinforcing the gap.

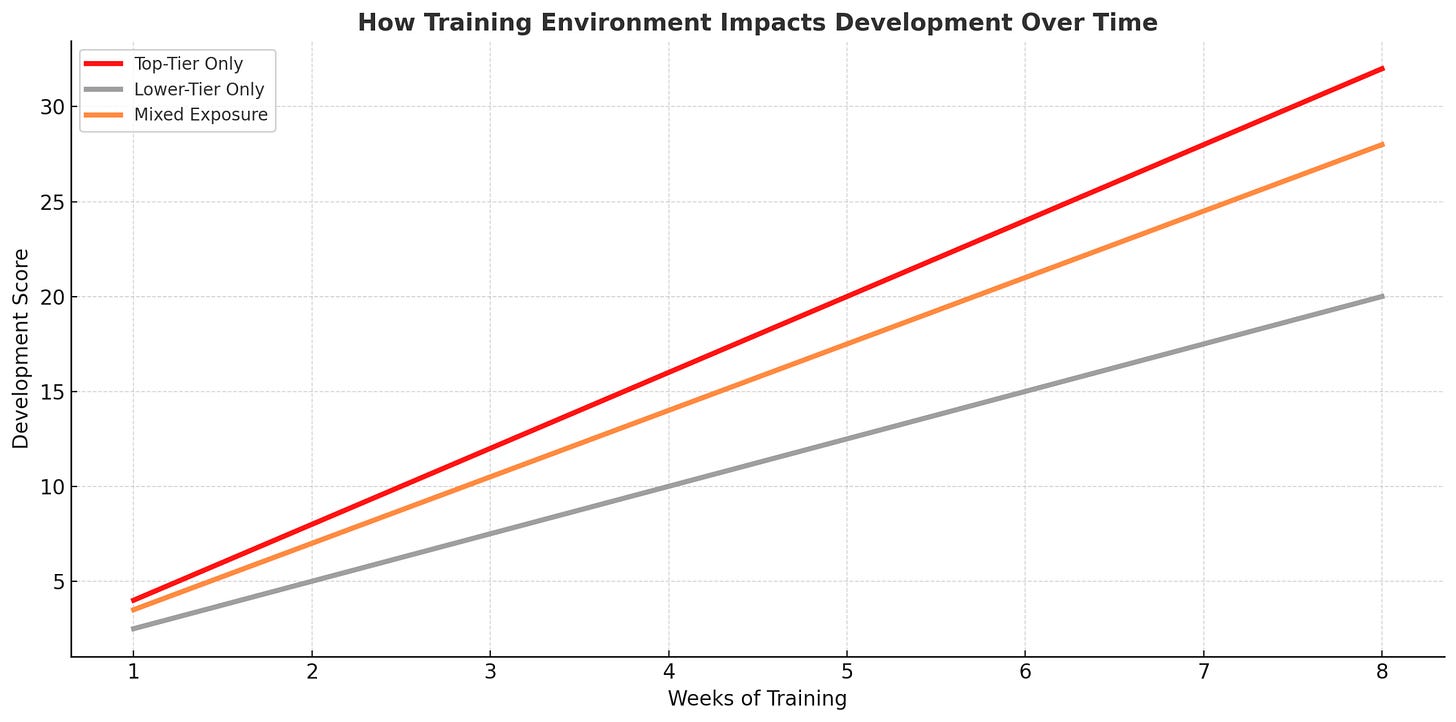

Let’s say every player in a top-tier session improves 8 out of 10. In a lower-tier session, the rate might be 5 out of 10. If the better players train four times a week, they improve 32 points. The others — even with the same training volume — improve only 20. And if one of those second-tier players gets just one first-team session a week? Maybe they hit 29. Close. But not quite enough.

Then we tell ourselves, “They’re just not improving fast enough.”

Of course they’re not. The system was designed that way.

Can Players Still Make it Back?

I know there are valid reasons a player might not be in the top group at a certain moment. School can be overwhelming. Bodies develop unevenly. Some players just don’t see the game clearly yet — scanning, timing, decision-making still a beat behind. These things matter. But here’s what I’ve learned, often the hard way: most of those things are temporary. And almost all of them are trainable.

I’ve seen it — players who finally pass their exams and find freedom in their game. Late bloomers who return from summer looking like different people. Young talents who start watching video, who learn to see faster, think sharper, move with purpose. Some close the gap in months.

One still stands out. A German U16 — early maturer, incredible timing, a presence on the field. He made the U19s that won Euros, looked destined for more. But as the others caught up physically, his edge faded. His habits didn’t keep pace. He missed the cut for the 2022 Euros. At that moment, he wasn’t good enough.

But he didn’t fold. He changed. Diet, lifestyle, mindset — he rebuilt it all. Slowly, steadily, he got back the edge. But this time, he brought the rest with him. Now? Junior World Cup winner. Men’s Indoor World Champion. MVP of the 2024 Junior Europeans. Senior team camp invitee. He didn’t just return. He redefined himself.

So yes — second chances can work. But they’re rare. Too rare for my liking. Most players don’t make it back. Because once they’re out of the environment, they’re out of the growth loop. Less challenge. Less feedback. Less exposure. And that limits what even the most motivated can achieve.

We have to confront that. If we want change, we have to start there.

Research by Till et al. (2016) backs this: players outside elite environments simply get fewer chances to build the tools they’ll need later — often leading to stagnation or dropout.

A Shift in Perspective: Reimagining Development

In my time as boys’ pathway manager — and later head of youth development — at Amsterdamsche Hockey & Bandy Club (AH&BC), I ran headfirst into a system that pushed us to sort kids too early. For U14s, the first six games weren’t just fixtures — they were qualifiers. Win enough, and you’d secure a place in the top tier. Lose early, and the rest of the season you’d be playing below your potential. That pressure meant we often leaned toward picking players who were bigger, faster, further along physically — not always the most talented, but the most ready in that moment. And just like that, the pipeline started to narrow.

Even before that, players were being quietly graded — internal coefficients assigned by the federation to sort talent and create more “balanced” leagues. It sounded logical on paper: tight games keep kids motivated, help development. But that logic assumes every kid starts on equal footing — and they don’t. The early developers had the edge. And the late bloomers? They were judged too soon.

I remember 2015 vividly. Meetings where we debated whether a U10 should be grouped with “stronger” players, or whether to honour a parent’s wish to place their daughter with a friend. Then, it felt like routine. But something about it kept gnawing at me.

And then came the U12 dilemma. We had technically gifted boys — talented, creative, smart — but small. In order to qualify for the highest league, we had to get results in the first six games. But playing them meant risking results, because physically, they couldn’t dominate yet. We were stuck. Develop them or drop them. That’s when we stopped playing by the book.

We merged the first and second teams into a larger pool. It gave us more flexibility — in training, in selection, in how we matched kids to challenges. Smaller players trained with older, more developed peers. Pressure was eased. Lines between teams blurred. Selections became less definitive. And development — real development — could breathe again.

Four players who went through exactly that programme are now part of the team playing in the Hoofdklasse national final this weekend.

And let’s be honest: the kid spinning their stick like a helicopter at U9 isn’t less talented. They’re just being nine. At that age, discipline and drive have more to do with parenting than potential. If we use those early snapshots as verdicts, we’re judging futures through the wrong lens.

So we shifted things. We combined U14 teams to take pressure off. Rebuilt U12 training to focus on age and stage. Closed off early access for outside players to give our own more time. We weren’t protecting the system. We were protecting the kids.

That period changed how I coach — and how I think. Working alongside Thomas Immink and backed by a board that shared our vision, it felt like we were doing more than building players. We were redesigning a system. We tried to revolutionise our pathway.

I won’t pretend that change started with me. But I see the echoes of it now in Dutch youth hockey. And it makes me proud to see an idea that I can identify with come through more in the country I am from.

This approach may sound idealistic. In today’s world, early wins build profiles. Results bring status. Patience feels outdated.

But maybe that’s why it matters more than ever.

If we truly care about development — not just selection — then we need to stop sorting too early. Stop mistaking early polish for real potential. Let them stay in the game longer. Let them stumble. Let them stretch. Let them show us who they can become — not just who they are today.

Lessons from Germany

One reason I felt so aligned with the German model — and still do — is their deliberate, layered approach to selection. It’s broad by design. What started as a logistical need, due to the country’s size, turned out to be a beautiful coincidence — one that gave their youth players time, space, and chance.

When I was Pathway Lead (Bundestrainer Nachwuchs) at the Deutscher Hockey-Bund e.V. (DHB) , I stepped into a system already well thought through. Talent wasn’t identified on one-off performances, but through multiple touchpoints. The Länderpokal — Germany’s inter-state championships — was just one layer. National championship qualifiers and finals were scouted. And recruitment camps brought talent from across the country together to train and compete.

Altogether, players had around 14 different contact days a year to showcase themselves before they were even brought into the pathway. And once selected, their progress was monitored across another dozen days annually — all outside of national team camps. Multiple settings. Multiple observers. It gave us a fuller view of a player's growth curve — not just snapshots.

It made me rethink: what defines a great pathway? Is it how strong the top players are? Or how few slip through the cracks?

The Germans also had systems in place to avoid burnout and early acceleration. U16s couldn’t play senior club hockey. No matter how talented, they stayed with their own age group. No 15-year-olds pushed into adult teams. It protected them physically — but also mentally. They weren’t being rushed.

And they built in second chances. The 'Nachsichtung' — a re-selection moment at U18 — explicitly acknowledged late bloomers. Development isn’t linear, and they structured for that.

Even league systems reflected this mindset. Clubs could self-select their playing level. Team lists were fluid. Players could help out in older age groups. And because age groups played on different days, they didn’t have to choose. They could play both. It sounds simple — but it created room.

Indoor hockey was handled just as smartly. Instead of wedging it into a mid-season break, the youth outdoor season ended before indoor began. No January reshuffles. No kids dropped mid-year just as they were finding form. It was a different rhythm — but one that honoured the developmental process.

All of this also helped in achieving one goal in my eyes: keeping the pipeline open. Giving time. Giving space. Giving kids the chance to grow into who they could become.

The Berlin Case: Stretch Without Breaking

At Berliner Hockey-Club e.V., we applied those same principles — just with fewer resources. We weren’t paying players. The club’s values didn’t allow for it, so we had to find different ways to stay competitive in the Bundesliga. That meant: develop from within. Build a program, not just a team.

At one point, our squad had 36 players — a number most would call unmanageable. But we made it work. Once youth players turned 16 or 17, they joined the adult program. Under federation rules, four games at a certain level meant they couldn’t drop down again. So we had to be deliberate.

We rotated players carefully through the second and third teams, based on their development goals. We didn’t throw them in to sink or swim — but we didn’t hold them back either. They trained everything with the first team, but played where they could gain confidence, minutes, and learn without the pressure of perfection.

No one learns on the bench. That was our guiding belief. So interchange became our secret weapon — not just a rule, but a development tool. It allowed us to give young players real exposure, for short, intense bursts, without risking the outcome. They got a taste of the tempo, the challenge — and they grew because of it.

Let’s Be Real: Keeping the Pipeline Open

All those structural choices — big or small — aim to do the same thing: keep the pool wide, and talent breathing. That mindset is exactly what I’ve walked into with the Belgian Federation. Right now, seven U21 players train full-time with the Red Panthers. They’re not toggling back and forth — they’re part of our senior squad. As long as we’re building toward the 2026 World Cup, that’s where they belong. Only when the Junior World Cup comes into focus, and tactical prep begins, will they shift back. Until then? They’re in our environment. Growing. Contributing. Belonging. And that makes all of us better.

I’m not blind to the reality. In top-level sport, pressure is everywhere. Results matter. League systems, qualification rules, even funding models — they all push teams toward early selection and short-term gains. And I get it. If a player isn’t ready, the cost might be more than just a lost match. It could jeopardise a season. Or a program.

Then there’s the question of fairness. If you select someone who’s not the strongest right now, are you doing right by the rest?

I understand that tension. I’ve lived it.

But here’s what I believe: structures should inform us — not limit us. If you’re a coach, a performance lead, or even a club volunteer — don’t just play by the system. Shape it. Stretch it. Find leeway. Create space.

Because if we want to see who someone can become, we need to keep them in long enough to grow into that version. Selection isn’t the finish line. It’s just a checkpoint. Deselection shouldn’t shut the door — it should signal a detour. A different route forward.

The better we get at holding space for development, the more likely we are to be surprised — in the best possible way.

And that’s not just good for the individual. It’s good for the game.

A final note.

I want to be clear: I do not oppose selection. It has its place in sport, and in high-performance environments, it’s often necessary. But what I do challenge — firmly — is the age at which we start selecting, and the assumptions we build into those decisions. Because with every choice, there are consequences. And if we don’t pause to reflect on the casualties of our process — the players we overlook, the pathways we quietly close — then we’re not truly serving development. We’re simply narrowing the path far too soon.

About Rein van Eijk

Red Panthers Head Coach | Culture, coffee & counterpress | Helping good players become great teammates | One pass at a time

Previous masterclass with Rein van Eijk ↓

Diversity is a superpower

Diversity is a superpower. In the coaching staff of todays topteams you will often find a lot of diversity. Rein van Eijk says it’s a superpower for these teams.

Interested in development pathways?

Make sure to join us when we go live with a new masterclass by GB coaches Jon Bleby and Mark Bateman ↓