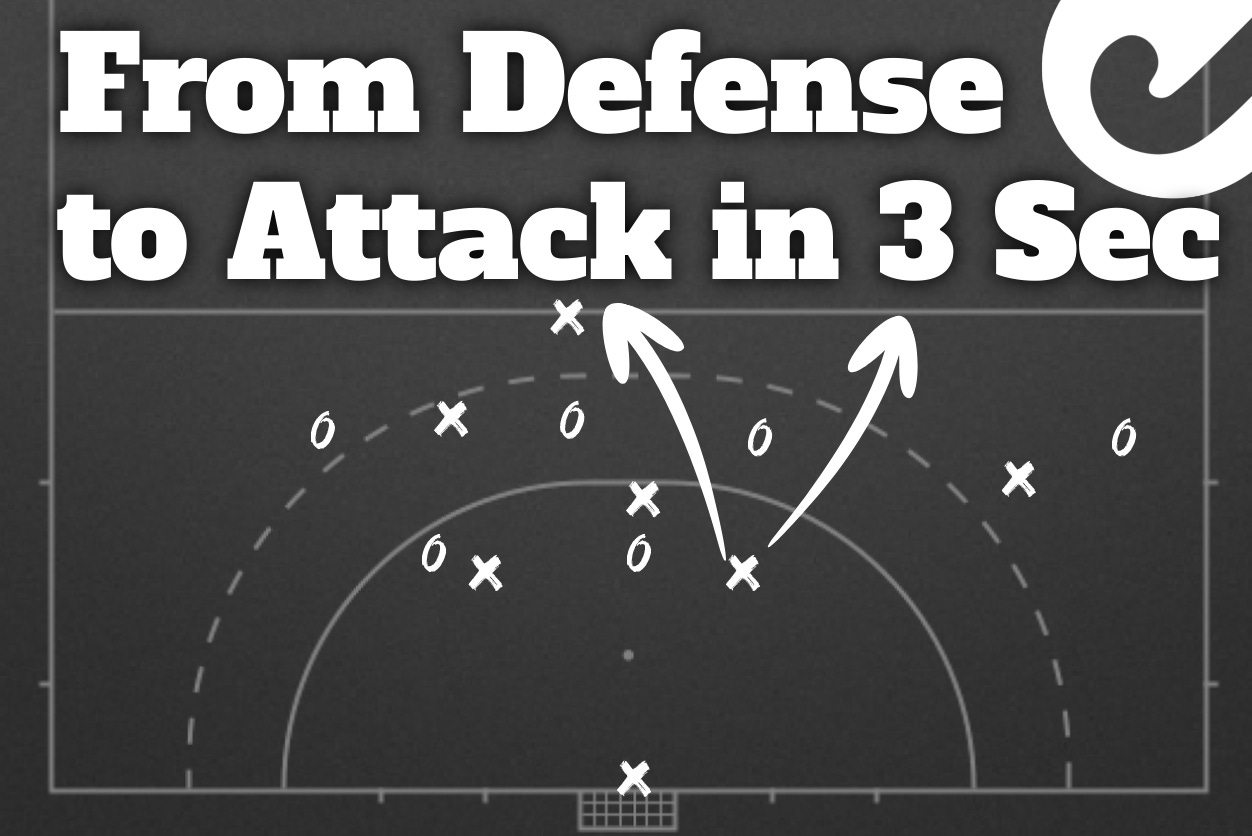

From Defense to Attack in 3 Seconds

How elite field hockey teams turn defensive moments into scoring opportunities before the opposition can recover

You’ve just won the ball back. Your opponent is scrambling. Their shape is broken, defenders are out of position, and for a fleeting moment, the entire field is yours for the taking. But here’s the thing: that moment lasts about three seconds. Maybe less.

In field hockey, the transition from defense to attack is the most dangerous phase of play—not just for your opponents, but for you if you don’t handle it right. It’s where games are won and lost, where the best teams separate themselves from the rest, and where individual brilliance meets tactical discipline.

Let’s break down why those first three seconds after winning possession are so critical, and more importantly, how you can train yourself and your team to exploit them.

Why Transitions Matter More Than You Think

Modern field hockey is faster than ever. Teams press higher, recover quicker, and close down space in the blink of an eye. The days of methodically building attacks from the back are gone—or at least, they’re no longer enough on their own.

As Andreu Enrich puts it, the key is being able to “recognize the moment” and “play at the right speed.”[1] When you win the ball, your opponents are momentarily disorganized. Their press has failed, their defensive structure is compromised, and they’re in recovery mode. But this window closes fast.

Ben Bishop emphasizes this when talking about defensive systems: teams that press high are inherently vulnerable in transition because they commit numbers forward.[2] If you can break that press and transition quickly, you’re playing against a defense that’s scrambling, not set. That’s where the magic happens.

But speed alone isn’t enough. Fede Tanuscio points out that against compact defenses, you need to be “patient but also ready to accelerate when the space appears.”[3] The art of the transition is knowing when to go fast and when to hold, reset, and probe.

The 3-Second Window: What Happens and Why

0-1 Second: Recognition

The moment you win possession, your brain needs to process the situation instantly. Where are the opponents? Where are your teammates? Is there space to attack? Is their defense still recovering?

This is where game intelligence separates good players from great ones. Robert Noall talks about the importance of “reading the game” and understanding when to exploit space versus when to be patient.[4] You can’t train speed of thought in a traditional sense, but you can train recognition patterns through repetition and video analysis.

1-2 Seconds: Decision

You’ve recognized the opportunity. Now you need to decide: Do I go forward immediately? Do I switch play? Do I take a touch to draw pressure and then release?

Russell Coates emphasizes that decision-making under pressure is crucial, particularly in the attacking third where “every action matters.”[5] The best transition attacks happen when players make simple, quick decisions that exploit the space they’ve identified.

Here’s the key: the decision should be made before you receive the ball. Elite players are constantly scanning, constantly processing. By the time the ball arrives at their feet, they already know what they’re going to do with it.

2-3 Seconds: Execution

This is where it all comes together. The ball is moving forward, teammates are running into space, and you’re executing the plan. If you’ve done everything right, your opponents are still recovering, and you’re attacking with numbers, speed, and purpose.

But if you’ve hesitated, taken an extra touch, or made the wrong decision, that window has closed. The defense has recovered, the press is back on, and you’re playing against a set defense again.

The Mental Game: Switching from Defender to Attacker

One of the hardest things to coach—and to master—is the mental switch that happens in transition. When you’re defending, your mindset is reactive: stop the attack, win the ball, protect the goal. But the moment you win possession, you need to flip a switch and become proactive: create danger, exploit space, score.

This doesn’t come naturally to everyone. Some players are so focused on their defensive responsibilities that they struggle to shift into attack mode quickly enough. Others are so eager to attack that they force plays that aren’t there.

The solution? Train transitions explicitly. Don’t just practice attacking drills or defensive drills in isolation—practice the moment between them. Create scenarios where players have to defend, win the ball, and immediately attack.

Make it chaotic, make it fast, and make it realistic.

Three Types of Transition Scenarios

1. The Counter-Attack: Full Speed Ahead

This is the classic scenario: you win the ball deep in your own half, your opponents are caught high up the field, and you have space to run into. This is where speed kills.

The key is simple decision-making: get the ball forward fast, support the ball carrier, and don’t over-complicate things. A long pass, a quick dribble, a one-two—whatever gets you into dangerous areas before the defense recovers.

2. The Numerical Advantage: Exploiting Overloads

Sometimes the transition doesn’t give you wide-open space, but it does give you a numbers advantage—3v2, 4v3, even 2v1. This is where intelligent movement and quick combinations win.

The mistake teams make here is slowing down too much. Yes, you have an advantage, but it only lasts a few seconds. Move the ball quickly, stretch the defense, and finish before help arrives.

3. The Half-Transition: Patience with Purpose

Not every transition is a sprint. Sometimes you win the ball but the space isn’t there yet. Maybe the defense recovered quickly, or maybe you’re facing a deep block that didn’t commit many numbers forward.

In these situations, you need to transition into a patient attacking phase-but stay alert for when the space does appear. Fede Tanuscio’s point about being “ready to accelerate when the space appears” is crucial here.[3] Don’t force the counter, but don’t let the opportunity slip away either.

Training the Transition

So how do you actually get better at this? Here are three practical training ideas:

Small-Sided Games with Instant Transitions

Set up 5v5 or 6v6 games on a half-field. When a team wins the ball, they have five seconds to get a shot on goal. If they don’t, the ball goes to the other team. This forces players to recognize opportunities and make quick decisions under pressure.

1v1 to 2v1 Progression

Start with a 1v1 scenario. When the defender wins the ball, a second attacker joins, creating a 2v1 going the other way. This trains the mental switch from defending to attacking and forces players to exploit the numerical advantage quickly.

Video Analysis: Identify the Moments

Watch game footage—your own or professional matches—and identify transition moments. Pause the video at the moment possession changes hands and ask: What’s the opportunity here? What should the player do? Then watch what actually happens and discuss whether the opportunity was exploited.

Common Mistakes in Transition

Taking Too Many Touches

The number one killer of transition attacks is hesitation. An extra touch, a moment of indecision, and the window closes. Train players to make quick, confident decisions—even if they’re not always perfect.

Forcing the Play

On the flip side, some players try to do too much. They see the opportunity and try to beat three defenders or attempt a killer pass that’s not on. Simple is fast, and fast is deadly in transition.

Not Supporting the Ball Carrier

Transitions are team efforts. If the player who wins the ball looks up and has no options, the attack dies. Train players to recognize when their team wins possession and sprint to support—even if they’re not directly involved in winning the ball.

Ignoring the Reset Option

Not every transition will work. Sometimes the defense recovers, sometimes the space wasn’t really there. The best teams know when to reset, keep the ball, and build patiently rather than turning it over by forcing a dead attack.

The Bottom Line

Transitions are where games are won. The team that can recognize opportunities fastest, make decisions quickest, and execute with precision in those first three seconds will create more chances, score more goals, and win more games.

It’s not about being the fastest team on the field—it’s about being the smartest in those crucial moments when possession changes hands. Train it, practice it, and make it a core part of your tactical identity.

Because in modern field hockey, three seconds is all you need. The question is: are you ready to use them?